Private equity and strategic buyers aren't the only suitors pursuing family businesses today.

Family offices, those low-key organizations formed to manage the wealth of ultra-high-net-worth families, are discreetly wooing business families who might be interested in selling a stake.

“Families that have built and grown successful businesses are increasingly looking for opportunities to invest in [other] family-owned businesses,” says Irene Mello, director of the Direct Investing Network at Family Office Exchange (FOX), a network for wealthy families and their family offices.

“Families that have built and grown successful businesses are increasingly looking for opportunities to invest in [other] family-owned businesses,” says Irene Mello, director of the Direct Investing Network at Family Office Exchange (FOX), a network for wealthy families and their family offices.

This relatively recent development is part of a growing trend by family investment firms to allocate a portion of their assets to investments in operating businesses. The past 24 months have seen a big uptick in this “direct investment” by the family office sector, notes Russ D'Argento, CEO of Fintrx, which provides data and research on the family office sector to the private capital markets.

In FOX's 2017 Global Investment Survey, 57% of family offices reported being involved, in some fashion, in direct investing in operating businesses. It's safe to assume at least some of those investments are in family businesses. Most family offices are looking for deals under $1 billion. Almost all companies bought by family investment firms are private businesses, observers say.

To facilitate direct investing, the family office sector is beefing up its staffing. According to the FOX investment survey, 81% of family offices employ at least one full-time staffer to source and evaluate direct investments.

There are several reasons for the increase in direct investment. To begin with, family investment firms today are very sophisticated and have hired top-tier talent, D'Argento says. As savvy financial investors, they've become increasingly dissatisfied with the “2-and-20” fee model used by private equity funds — a 2% management charge and a 20% performance fee — says Angelo Robles, founder and CEO of the Family Office Association, a global membership community of successful families and single-family offices.

Family companies provide great cash flows and growth opportunities, explains Bobby Stover, Ernst & Young's Americas family office leader. Because public markets are extremely efficient today, it's harder to find growth opportunities there, he says.

A growing sector

Finally, there are just more family investment firms seeking opportunities nowadays. In 2016, there were at least 10,000 single-family offices worldwide, with at least half started within the previous 15 years, according to Ernst & Young's “Family Office Guide.”

“Family offices are arguably the fastest-growing investment vehicles in the world today.… The increasing concentration of wealth held by very wealthy families and rising globalization are fueling their growth,” the EY guide states.

This appears to be an opportune time for family business owners to consider family investment firms as a way to raise capital.

|

Special Section: The quest for liquidity Creating shareholder liquidity: A checklist before going public Succession plans must incorporate liquidity planning for the family |

“It is becoming well known that families are looking to invest in private companies at the same time many family-owned companies are looking for capital from private investors to help solve their own transition issues,” says Sara Hamilton, FOX’s founder and CEO.

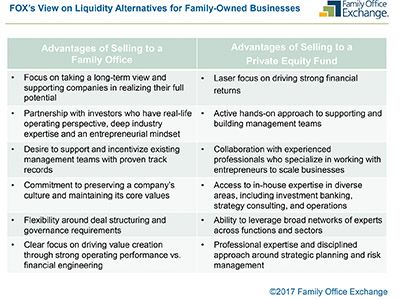

In the past, family businesses generally had two choices — selling to a strategic acquirer (often a competitor) or to a private equity fund, says Paul Carbone, managing partner of Pritzker Group Private Capital, a family investment firm.

Family office represents a third option, Carbone says.

For family business owners, a family investment group could provide flexible capital with an investment tailored to their individual situation, Carbone says. He says Pritzker likes to think of it as pulling on the oars together.

For example, many wealthy families have run businesses themselves.

“These families have real-life operating experience and therefore special insight into what it's like to run a family business and what's needed to drive strong performance,” Mello says. “This perspective gives them a real edge as investors, as they understand the needs of family businesses, relate to the challenges they face and can provide advice and support that's value-add and action-oriented,” Mello says.

Family offices sometimes want a controlling stake to influence the direction of the company, but many are open to minority investments where “they can back a strong management team with a proven track record and provide growth capital to accelerate a strategic plan,” Mello says.

Since family investment groups place a lot of importance on evaluating management teams, they're showing greater flexibility around deal structures and a higher interest in growth capital, Mello notes.

Aligned interests

In addition, family offices tend to understand the culture of the families they do business with, Stover says. For a family office, the term “long term” means generations, not seven to 10 years, he points out.

“It's sticky capital,” says D'Argento. “They hold and keep investments until it's appropriate to exit them. There's less of an institutional feel, and it's a bit more personal.”

Take Vincent Mai, who spent more than 20 years in private equity. Mai says he found it frustrating “to be selling really good businesses I didn't want to sell, and I saw the need for an alternative structure.” In 2012, he founded The Cranemere Group, a private holding company backed by family offices that acquires and holds family businesses for the long term.

Lansing Crane, former chairman and CEO of Crane Currency, which partnered with private equity in 2008, thinks family offices provide distinct advantages. “I think they're a great solution,” he says.

But 10 years ago, family office wasn't an option for his family business, Crane says.

“Most of the time, a strategic single-family office is much better than private equity because there's an alignment of interests,” says Robles.

But because the family office sector is so discreet, finding a partner can take work, say those in the field.

“It's a fragmented, cloudy world,” D'Argento says.

Patricia M. Soldano, a consultant with GenSpring Family Offices, suggests that family business owners join a network and attend conferences to learn what the various family offices do.

“It's hard. There's no list [of family offices seeking investments],” Soldano acknowledges.

Stover agrees most connections between family enterprises and family office happen through networking.

“It's known as ‘quiet capital,'” he says.

Maureen Milford is a business writer based in Wilmington, Del.

Copyright 2018 by Family Business Magazine. This article may not be posted online or reproduced in any form, including photocopy, without permission from the publisher. For reprint information, contact bwenger@familybusinessmagazine.com.