The boards of family businesses must find the proper balance between compensation for the management team working in the business and earnings for the family shareholders who own the business. It is likely that some family members will wear both hats, which heightens the challenge of distinguishing the return on labor (management) from the return on capital (shareholders).

The good news is that a healthy and well-performing family business will be able to fund both management compensation and shareholder earnings. A properly structured management compensation plan is based on performance measures and goals that are aligned with the objectives of family shareholders.

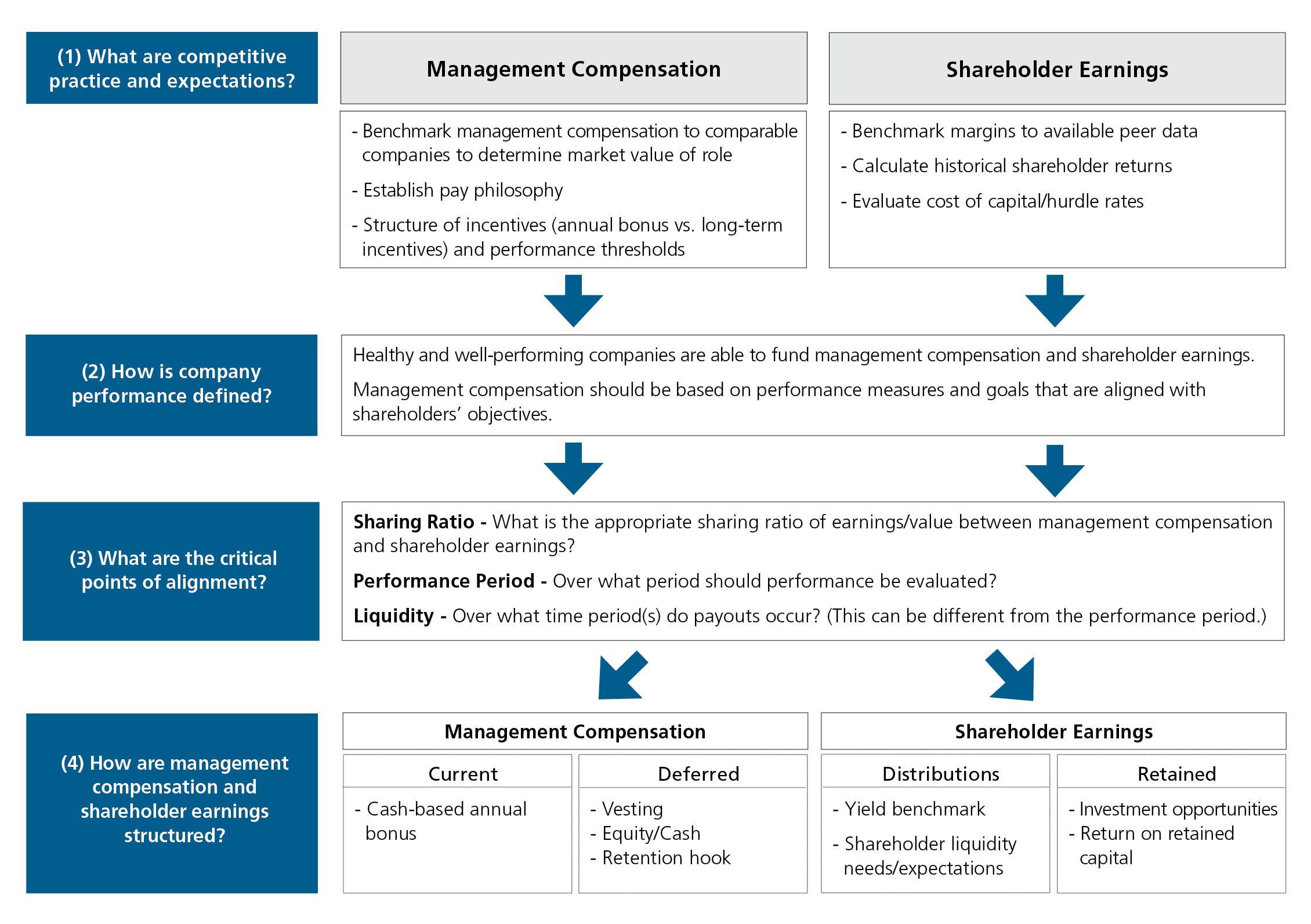

Evaluating your management compensation program to ensure it strikes the right balance between management compensation and shareholder earnings involves answering four main questions:

1. What are competitive practices and expectations with respect to management pay and shareholder returns?

2. How is company performance defined?

3. What are the critical points of alignment?

4. How are management compensation and shareholder earnings structured?

1. What are competitive practices and expectations?

• Management compensation: Providing a competitive compensation package is important to attract and retain a high-performing management team, especially if family members decide not to be owner-operators. Executives are in the marketplace every day, recruiting and talking to contemporaries, so they understand their value in the market. Therefore, companies should annually benchmark management compensation to market pay levels to ensure their pay programs remain competitive. Determining a comparable peer group of companies can be challenging, especially for privately held companies; however, published compensation surveys are available that cover specific industries and private company pay practices.

Once the board understands the market level of compensation, it can establish a pay philosophy that supports the  company's strategy. A pay philosophy sets the guiding principles that govern pay decisions and includes statements about the desired positioning of total pay relative to the market (e.g., median, third quartile), and the desired mix of fixed (salary) and variable (bonus and long-term incentives) compensation. In our experience, privately held companies tend to weigh cash compensation (salary and bonus) more heavily than long-term incentives, given the illiquidity of shares in private companies and the family's desire to retain control. However, long-term incentives are prevalent. Approximately 60% of private companies provide long-term incentives, according to a CAP-WorldatWork survey on private company incentive pay practices. The key is to align incentive awards with the family's financial and non-financial objectives for the business.

company's strategy. A pay philosophy sets the guiding principles that govern pay decisions and includes statements about the desired positioning of total pay relative to the market (e.g., median, third quartile), and the desired mix of fixed (salary) and variable (bonus and long-term incentives) compensation. In our experience, privately held companies tend to weigh cash compensation (salary and bonus) more heavily than long-term incentives, given the illiquidity of shares in private companies and the family's desire to retain control. However, long-term incentives are prevalent. Approximately 60% of private companies provide long-term incentives, according to a CAP-WorldatWork survey on private company incentive pay practices. The key is to align incentive awards with the family's financial and non-financial objectives for the business.

• Shareholder earnings: Shareholder earnings are either distributed or reinvested in the family business. Distributions allow family shareholders to fund lifestyle expenditures, build liquid reserves or invest in other assets for diversification. In contrast, reinvested earnings promote the growth of the family business, helping to build value for future generations of the family.

Families should determine the proportion of earnings to be distributed annually versus reinvested in the business. External market benchmarks can be informative inputs to the decision-making process. Industry associations and public companies in the same industry as the family business provide a wealth of operating and financial data such as quarterly earnings, dividend returns and company stock appreciation that can help inform shareholders as to competitive returns in the marketplace.

This competitive market data is one factor used to determine the shareholders' short- and long-term financial goals. Other factors include the company's long-range financial plan and a consensus around shareholder expectations of annual dividends. The ultimate outcome is a return policy that outlines the annual dividend policy and long-term capital appreciation goals, which are good starting points for establishing the performance standard for management incentive plans.

With a preliminary view of the competitive market for both labor and capital returns in hand, directors can then turn their attention to the metrics that will be used to specify the terms of a management incentive plan.

2. How is performance defined?

In our experience, three basic measures provide a great starting point for determining financial performance targets for annual and long-term incentive plans.

a. Profit margins. A profit margin is a ratio of earnings to revenue. Profit margins measure the operating efficiency of a business. The higher the profit margin, the more efficiently a business can convert revenue into profits. Since management compensation is a component of operating expense, profit margins shed light on the relative sharing between managers and shareholders.

b. Historical shareholder returns. Returns measure shareholder benefit per unit of investment. Shareholder benefits come in two forms: current income (dividends funded from earnings) and capital appreciation (growth in share price).

c. Cost of capital / hurdle rates. Historical returns are handy for evaluation of prior performance, but it is also essential to have a means of looking forward. Evaluating the cost of capital for your family business allows directors  to move beyond identifying the returns shareholders have earned in the past to the more critical question of what returns shareholders should earn in the future. The cost of capital is essentially the opportunity cost shareholders bear for allocating their capital to the family business rather than to other investments. As such, it can be used to help directors to assess the financial feasibility of proposed investments as well as to evaluate the relative sharing of benefits between managers and shareholders.

to move beyond identifying the returns shareholders have earned in the past to the more critical question of what returns shareholders should earn in the future. The cost of capital is essentially the opportunity cost shareholders bear for allocating their capital to the family business rather than to other investments. As such, it can be used to help directors to assess the financial feasibility of proposed investments as well as to evaluate the relative sharing of benefits between managers and shareholders.

We recommend analyzing all these metrics to formulate appropriate financial performance targets for management incentive plans. Depending on the robustness of the available data and the unique attributes of your family business, you can consider other performance measures to supplement these primary measures. Increasingly, environmental, social and governance metrics are being considered, as managing these risks is important to both building and protecting company value.

3. What are the critical points of alignment?

To ensure alignment between management compensation and shareholder earnings, three points should be addressed:

• What is the appropriate “sharing” ratio of earnings or company value between owners and management? On an annual basis, shareholders share a portion of profits with management and employees in the form of annual bonuses. On a multiyear basis, shareholders share a portion of company value with management in the form of long-term incentives. Boards can calculate both sharing ratios and analyze the total dollars shared with management (in aggregate and by individual role). These ratios can be compared with market pay levels to ensure that the total dollar amounts are competitive.

In our experience, the sharing ratio for long-term incentives increases with the likelihood of a monetization event. Shareholders may need to offer healthy long-term incentives to recruit an outside executive team that can grow the company and prepare it for sale. For companies that intend to stay family-owned for the long term, CAP's research finds that sharing ratios of long-term incentive plans tend to be less than 10% of company value.

While owners may have an initial idea of how much they are willing to share with employees, it is useful to model the possible outcomes of potential incentive programs early in the design process. This enables owners to understand not only the financial and ownership implications, but also how meaningful the opportunity is to the management team. In our experience, shareholders want certainty — knowing the maximum dollar exposure or aggregate sharing ratio — whereas management wants to understand the earning potential and prefers an uncapped dollar opportunity.

• What is the time period over which performance is measured? Because incentive programs should meet the family's objectives over a certain time horizon, matching the incentive performance period to owners' planning horizons makes sense. As mentioned above, shareholder returns come from current income (annual dividends) and capital appreciation. As a result, creating two separate incentive plans for management — an annual bonus for yearly performance and a long-term incentive plan for long-term company growth — aligns with the dual time horizons of the owners. The weighting of short- versus long-term incentives can be altered depending on the type of return preferred by shareholders. Overall, CAP's research shows that the time horizons for long-term incentives tend to be five years (or more).

* What are the liquidity provisions? While annual incentive plans have yearly payouts, long-term incentive plans can center on various liquidity mechanisms and payout time horizons. In some incentive plans, the performance period and payout timing coincide. For companies that experience a monetization event, liquidity typically occurs for both owners and management when the deal is closed. In companies the family plans to pass to the next generation, performance period and liquidity do not have to be synchronous. If the performance period can be defined (e.g., five years), the award value is calculated at the end of the period. Alternatively, payout can occur in installments (e.g., half at the end of year five, half at the end of year six). Installment payments help owners with cash flow management and promote management retention. Modeling the accounting and cash flow of expected incentive payouts under different performance scenarios is prudent financial planning. In addition, thoughtful incentive plans are structured to include “safety valves” whereby payouts can be limited or deferred to ensure company financial stability.

4. How are management compensation and shareholder earnings structured?

Families should be deliberate in defining the percentage of earnings to be distributed versus reinvested. These decisions help guide the timing of management incentive plan payouts. While the textbook answer is simple — earnings should be reinvested if they can earn a return exceeding the cost of capital — the facts on the ground are often much messier. In many families, shareholders assign greater value to current cash distributions than to the prospects of a higher terminal value at some uncertain future liquidity event (which may not even occur during their lifetimes). At the same time, management should receive payouts for creating long-term company value during their employment tenure. This tension can be particularly acute if the family members who are also managers of the business are enjoying incentive-based cash bonuses. If one member of the family enjoys an immediate return on her labor, why should another one wait indefinitely to realize the return on his capital?

As is often the case in family businesses, communication is critical. Family shareholders crave transparency and predictability. When crafting a management incentive plan, directors should understand that shareholders will want to compare how the incentive benefits stack up to shareholder earnings, especially regarding timing and composition of returns. Just as managers need to understand the parameters of their compensation plan, shareholders need a clear vision of the tradeoffs between current and future returns they are being asked to make. Clear explanations of how the incentive plans work, the sharing ratios between management and shareholders, and projected incentive award values and payout dates allow family shareholders to understand how well the management incentive plans are aligned with their objectives.

Bertha Masuda is a partner in Compensation Advisory Partners LLC and Travis Harms is senior vice president at Mercer Capital.

Copyright 2021 by Family Business Magazine. This article may not be posted online or reproduced in any form, including photocopy, without permission from the publisher. For reprint information, contact bwenger@familybusinessmagazine.com.